A volcanic eruption 39 million years ago buried a forest in Peru – now the petrified trees are revealing South America’s primeval history

Jun 9, 2021

In the hills outside the small village of Sexi, Peru, a fossil forest holds secrets about South America’s past millions of years ago.

When we first visited these petrified trees more than 20 years ago, not much was known about their age or how they came to be preserved. We started by dating the rocks and studying the volcanic processes that preserved the fossils. From there, we began to piece together the story of the forest, starting from the day 39 million years ago when a volcano erupted in northern Peru.

Ash rained down on the forest that day, stripping leaves from the trees. Then flows of ashy material moved through, breaking off the trees and carrying them like logs in a river to the area where they were buried and preserved. Millions of years later, after the modern-day Andes rose and carried the fossils with them, the rocks were exposed to the forces of erosion, and the fossil woods and leaves again saw the light of day.

This petrified forest, El Bosque Perificado Piedra Chamana, is

the first fossil forest from the South American tropics to be studied in detail. It is helping paleontologists like us to understand the history of the megadiverse forests of the New World tropics and the past climates and environments of South America.

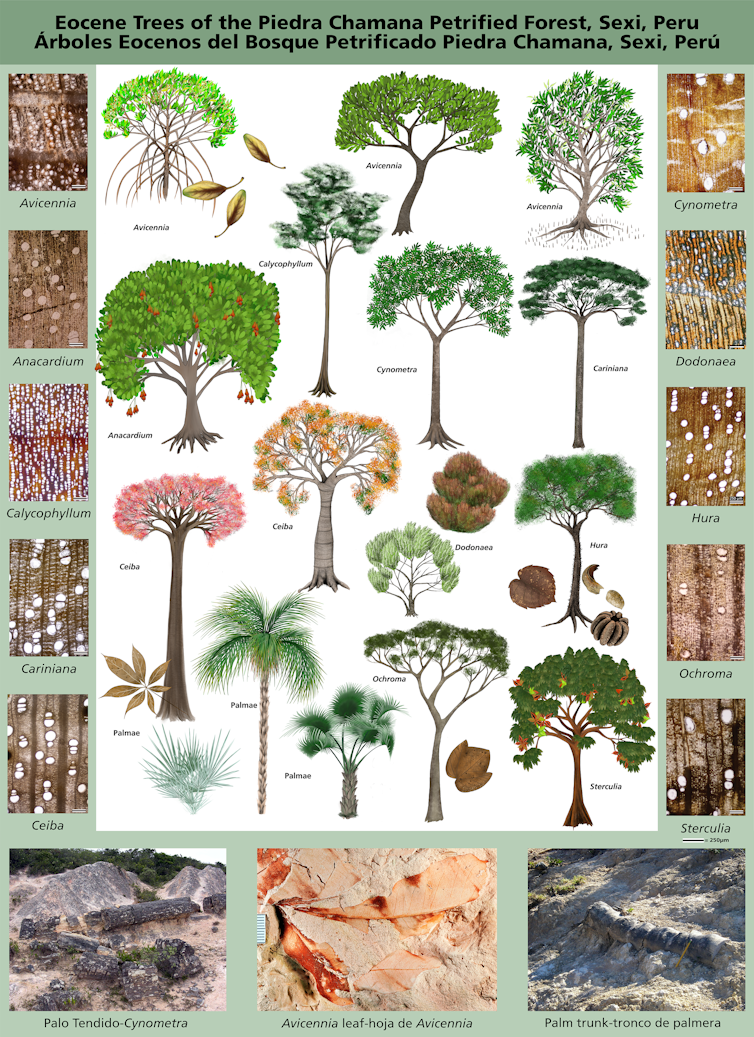

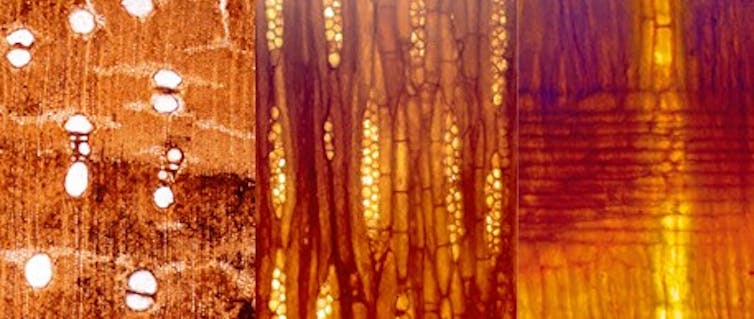

By examining thin slices of petrified wood under microscopes, we were able to map out the mix of trees that thrived here long before humans existed.

Mariah Slovacek/National Park Service, CC BY-ND

Petrified wood under a microscope

To figure out the types of trees that had been growing in the forest before the eruption, we needed thin samples of the petrified wood that could be studied under a microscope. That was not so easy because of the volume and diversity of fossil wood at the site.

We tried to sample the diversity of the woods by relying on features that could be observed with the naked eye or with small hand-held microscopes, things like the arrangement and width of the vessels that carry water upwards within the tree or the presence of tree rings. Then we cut small blocks from the specimens, and from those we were able to prepare petrographic thin sections in three planes. Each plane gives us a different view of the tree’s anatomy. They allow us to see many detailed features relating to the vessels, the wood fibers and the living-tissue component of the wood.

Woodcock et al. 2017, CC BY-ND

Based on these features, we were able to consult past studies and use information in wood databases to find out what types of trees were present.

Clues in the woods and leaves

Many of the fossil trees have close relatives in the present-day lowland tropical forests of South America.

One has features typical of lianas, which are woody vines. Others appear to have been large canopy trees, including relatives of modern Ceiba. We also found trees that are well known in the forests of South America like Hura, or sandbox tree; Anacardium, a type of cashew tree; and Ochroma, or balsa. The largest specimen at the Sexi site – a fossil trunk about 2.5 feet (75 cm) in diameter – has features like those of Cynometra, a tree in the legume family.

The discovery of a mangrove, Avicennia, was more evidence that the forest was growing at a low elevation near the sea before the Andes rose.

The fossil leaves we found provided another clue to the past. All had smooth edges, rather than the toothed edges or lobes that are more common in the cooler climates of the mid- to high latitudes, indicating that the forest experienced quite warm conditions. We know the forest was growing at a time in the geologic past when the Earth was much warmer than today.

National Park Service, CC BY-ND

Although there are many similarities between the petrified forest and present-day Amazonian forests, some of the fossil trees have anatomical features that are unusual in the South American tropics. One is a species of Dipterocarpaceae, a group that has only one other representative in South America but that is common today in the rainforests of South Asia.

An artist brings the forest to life

Our concept of what this ancient forest was like expanded when we had an opportunity to collaborate with an artist at Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument in Colorado to reconstruct the forest and landscape. Other locations with fossil trees include Florissant, which has giant petrified redwood stumps, and Petrifed Forest National Park in Arizona.

Working with the artist, Mariah Slovacek, who is also a paleontologist, made us think critically about many things: What would the forest have looked like? Were the trees evergreen or deciduous? Which were tall and which shorter? What would they have looked like in flower or in fruit?

We knew from our investigation that many of the fossil trees were likely to have been growing in a streamside or flooded-forest location, but what about the vegetation growing back from the watercourses on higher ground? Would the hills have been forested or supported drier-adapted vegetation? Mariah researched today’s relatives of the trees we identified for clues to what they might have looked like, such as what shape and color their flowers or fruits might have been.

National Park Service, CC BY-ND

No fossils of mammals, birds or reptiles from the same time period have been found at the Sexi site, but the ancient forest certainly would have supported a diversity of wildlife. Birds had diversified by that time, and reptiles in the crocodile family had long swum the tropical seas.

Recent paleontological discoveries found that two important groups of animals – monkeys and caviomorph rodents, which include guinea pigs – had arrived on the continent at about the time the fossil forest was growing.

With this information, Mariah was able to populate the ancient forest. The result is a lush, waterside forest of tall flowering trees and woody vines. Birds swoop through the air and a crocodile splashes just offshore. You can almost imagine that you were there in the world of 39 million years ago.

![]()

Deborah Woodcock has received funding from the American Philosophical Society, the National Science Foundation, and National Geographic.

Herb Meyer has been supported in this project as an employee of the National Park Service, with additional funding provided by The Friends of the Florissant Fossil Beds, the National Science Foundation, and National Geographic.