Shedding Light on Urban Development

Nov 15, 2021

In the past 20 years, astronauts on the International Space Station (ISS) have shot millions of photographs of Earth. The collection offers more than just remarkable views of our home planet; it is a valuable tool for researchers. Christopher Small, of Columbia University, has found the nighttime images to be especially illuminating. By analyzing images of Earth at night, he is working to gain insight into how cities grow and evolve.

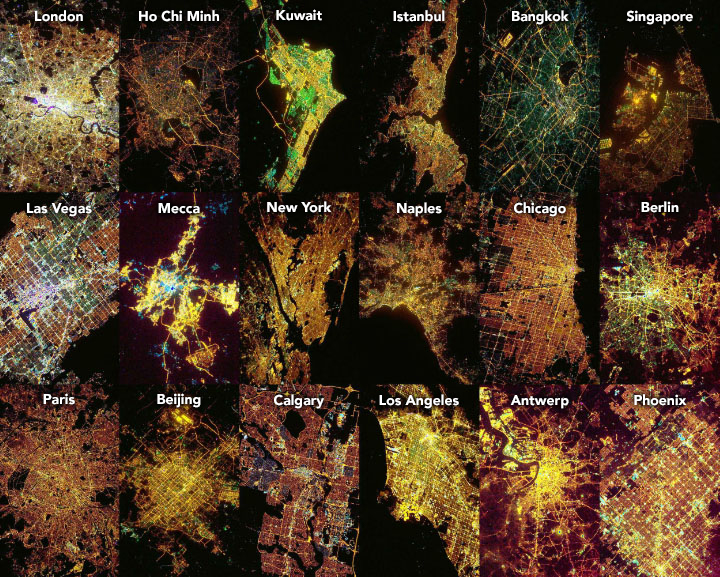

Small has been working to characterize the different types of lighting used across a variety of urban areas. Specifically, he wants to quantify things like the relative brightness, color, and areal abundance of different types of city lights. He has sorted through hundreds of photos of cities that were shot from the ISS, looking specifically for cities with lights in a wide range of colors and spatial configurations.

The montage above shows 18 cities—from London to Singapore to Phoenix—with especially diverse nighttime lightscapes. The images are also relatively high in resolution: Each was shot with a 400-millimeter lens capable of resolving individual lights. Small then calibrated each of the images to have the same color temperature, so they could be compared directly. This montage was calibrated to 5500 Kelvin—about the same color temperature as sunlight.

In general, the warmer orange and yellow colors in the photographs are likely high-pressure sodium lights. Chicago, for example, has long been known for its widespread orange glow. (That is starting to change in recent years, however, as the city swaps in more LEDs.) Cooler greens and blues are likely mercury vapor lights. LEDs could also be contributing to the color.

A key part of Small’s research has been trying to determine how much light comes from thoroughfares (highways and city streets) compared to individual lights (parking lot lights, façade lights, and billboards). He has found that “the light in urban environments comes almost entirely from outdoor lighting rather than from light transmitted from within buildings. And most of this light is on streets and roads.”

The ISS photographs of Paris (above) and Kuwait City (below) have been calibrated to a color temperature of 2200 Kelvin, typical of high-pressure sodium lights. These two cities display very different color and spatial configurations. Light in Paris comes almost entirely from streetlights—primarily yellow, but also blue and green. Avenue des Champs-Elysées appears white, likely because the brightness of the street lights and buildings saturated this part of the image. “Paris is probably the best example of the diversity of colors and spatial configurations that we are trying to quantify,” Small said.

In Kuwait City and surrounding neighborhoods, lighting in newer developments such as Abdullah Mubarak Al-Sabah appears green—likely mercury vapor streetlights. The brighter lights, surrounded by dimmer, more uniformly disibuted lights, are probably mosques.

The ability to resolve individual light sources and their color—from high resolution ISS photographs—together with repeat observations of night light brightness—from lower-resolution satellite sensors such as VIIRS—are helping scientists better understand urban growth. “The brightness and color of different types of lighting can help us distinguish different types of infrastructure related to the form and function of urban development,” Small said. “This informs our understanding of how spatial networks of development evolve during urban growth.”

Small says that research is already showing that lights in most cities tend to display common network structures and often “emerge without centralized planning or design,” which could imply that cities follow similar growth processes no matter where they are. “The suggestion that the process of emergent behavior seems to be similar in cities all over the world is interesting in itself,” Small noted.

Astronaut photograph ISS032-E-17635 (Kuwait City) was acquired on August 9, 2012, with a Nikon D4 digital camera using a 400 millimeter lens. The image was taken by a member of the Expedition 32 crew. Astronaut photograph ISS043-E-93480 (Paris) was acquired on April 8, 2015, with a Nikon D4 digital camera using a 400 millimeter lens. The image was taken by a member of the Expedition 43 crew. The images have been cropped, calibrated to common tint and white balance, and corrected for wavelength-dependent atmospheric transmission losses. Both photos were provided by the ISS Crew Earth Observations Facility and the Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, Johnson Space Center. Additional images taken by astronauts and cosmonauts can be viewed at the NASA/JSC Gateway to Astronaut Photography of Earth. Story by Kathryn Hansen.