Windblown Beauty in the Weddell Sea

Dec 8, 2021

The frozen blanket of sea ice atop the Southern Ocean is a study in extremes. After growing to cover as much as 18 million square kilometers of the sea in winter, the ice almost completely melts away each summer. But even during this annual melting, temperatures during the austral spring can still be cold enough to produce localized areas of new ice growth around Antarctica.

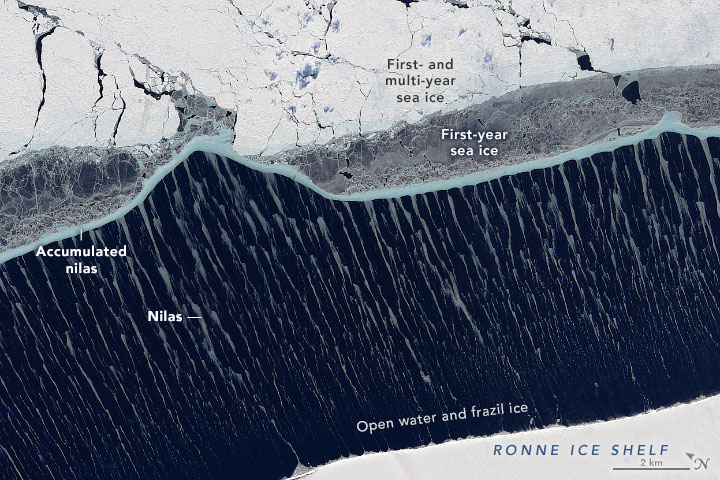

The result is a medley of frozen patterns and textures, visible in this image acquired on November 20, 2021, with the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8. It shows an array of ice types in the Weddell Sea close to the Antarctic continent.

The thickest ice in this view is not sea ice at all; it belongs to the Ronne Ice Shelf. The shelf is a floating extension of Antarctica’s land-based ice sheet, and extends tens of meters above sea level at its front. The same ice shelf calved Iceberg A-76 in May 2021. The iceberg pieces have since drifted outside the frame of this image.

Sea ice frequently hugs the ice shelf. But on this day, wind blowing out from the interior pushed the ice away, leaving a relatively wide strip of open water. It was cold enough that the water began to refreeze immediately, but winds continued to propel the new ice away from the shelf. As a result, the water closest to the shelf was likely a mix of open water mixed with frazil ice—tiny needle-like crystals that mark the very first stage of ice growth.

As frazil crystals connect and accumulate, they form nilas—young ice that often forms thin sheets, generally no more than 10 centimeters thick. But the nilas in this image is streaky, not sheet-like. According to Walt Meier, a sea ice scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center, winds have likely induced vortices in the layer of water closest to the surface, causing it to rotate vertically in small circular patterns perpendicular to the direction of the wind. In areas where these rotations converge, nilas ice has collected, creating the light-gray streaks amid the darker water.

Nilas that had traversed the opening became bunched up near the edge of the main ice pack, forming a thin blue-gray line. The blue color, however, is a curiosity. Glacier ice and sea ice usually appear blue when the ice has become so dense that it absorbs the longer wavelengths of light and only reflects the blue. “I’m not quite sure how the sea ice here gets the blue color,” Meier said, “but it’s possible the ice got compressed enough to cause that effect.”

Next, we see a distinct strip of gray ice, which Meier noted could be nilas or grease ice. Either way, the gray color is a clue that this is thin “first-year” ice—young ice that formed after the 2020-21 summer melt season.

Finally, beyond the gray patches we see the oldest and thickest sea ice. Meier thinks this is likely also first-year ice, but he notes that the Weddell Sea is known to contain some multi-year ice that has survived at least one summer melting season. “Either way, this is ice that has been around since at least the beginning of the ice growth season back in March or April and is a meter or more thick,” he said. But even this older, thicker ice is not immune from the effects of the wind. The relentless pushing has caused the ice to fracture, visible as the network of dark areas and lines across the otherwise white expanse.

Despite the small amount of growth and the captivating patterns, sea ice across the Weddell will continue to wane as the melting season progresses. So far around all of Antarctica, three months after the start of the seasonal decline, the sea ice extent in November 2021 was well below the 42-year average for the time of year.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Kathryn Hansen, with information and image interpretation by Claire Parkinson/NASA GSFC and Walt Meier/NSIDC.